Organizing and Reflecting Different Types of Engagement Activities: The Michigan Public Engagement Framework

Elyse is the Public Engagement Lead at the University of Michigan’s Office of Academic Innovation. She is a scientist and science communicator. This post was co-written with her colleagues Ellen Kuhn, Public Engagement Specialist, and Rachel K. Niemer, Director of Strategic Initiatives.

Note from Jamie Bell, CAISE Project Director: CAISE has been tracking definitions and views of public engagement with science since releasing its first white paper on the topic in 2009.

Recently, we published a Knowledge Base article and an interview series with scholars who study engagement in a variety of settings. As the field continues to evolve, we welcome and share this new systems-level model, which has useful implications for the design, research, and evaluation of informal STEM learning environments and experiences.

Like many institutions of higher education, the University of Michigan embraces its public mission. This commitment was renewed in 2017, when President Mark Schlissel announced a strategic area of focus on public engagement. As part of this effort, the Office of Academic Innovation, a unit on campus that drives innovation in teaching and learning through online learning experiences, software tools, and data and learning analytics, was charged with fostering innovation by launching new experiments to reimagine public engagement, especially using digital tools.

In order to meet this challenge, we first needed to understand all the ways that the University of Michigan already engaged different publics—no small feat, given that there are over 170 units or programs supporting various engagement efforts, not counting the work that faculty and students pursue independently. (This challenge resonated with me deeply—I wished I’d had a better sense of my options when I was trying to navigate public engagement with science in graduate school at Michigan!)

Further complicating this charge was the observation that the words “public engagement” mean different things to different people. For example, professional communicators emphasize some aspects of public engagement, while scholars working in partnership with local communities focus on others. Performance and exhibition artists pursue different forms of engagement work than do people who are working to influence local and national policy. Museums engage visitors and families differently than do groups partnering with business communities. And yet these are all channels and approaches that the University of Michigan uses to engage different publics. We sought to understand: What are the important similarities, points of connection, and things we might learn from each other as we pursue different forms of public engagement work?

Our working draft of the Michigan Public Engagement Framework emerged from these explorations, and we hope that it will be useful to other institutions seeking to understand and describe public engagement efforts at a systems level. The framework can also be used by individuals to prepare for and guide engagement efforts.

The Framework

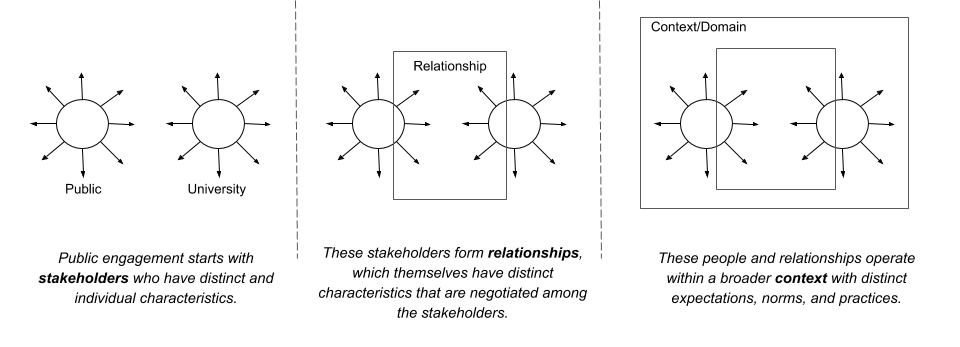

The Michigan Public Engagement Framework rests on three elements: people, relationships, and context. In describing these three elements, we can begin to understand the unique facets of any engagement effort, as well as to consider points of similarity.

Step 1: People

Both public and university stakeholders bring distinct and individual characteristics to the table. How might we describe all the parties involved?

Some characteristics are relatively static, including demographics, values and beliefs, historical contexts and inequities, group size, and group similarity. These are often the characteristics that scholars use to describe an audience.

At the same time, people also bring a set of variable characteristics that might change over time, including:

- Motivation to engage

- Formal decision-making power

- Informal power and influence

- Resources

- Knowledge and experience of (x) [requires naming (x)]

- Experience with the other stakeholders

- Perception of the other stakeholders

- Communication skills

- Openness to relationships with others

- Risks and barriers

Describing and measuring this same set of characteristics for each stakeholder is likely to yield very different—and very informative—images. These pictures enable us to think more deeply about stakeholders as whole humans.

Step 2: Relationships

Any relationship that public and university stakeholders create also has descriptive and variable characteristics. Descriptive characteristics include needs, goals, and locality, while variable characteristics include:

- Directionality

- History of the relationship

- Recognition of knowledge and experience of (x) [requires naming (x)]

- Inclusivity and access

- Transparency and accountability

- Temporality of relationship

It is critical to negotiate these characteristics between all stakeholders as part of the relationship-building process.

Step 3: Context

The environment in which the relationship exists determines additional norms, expectations, constraints, and opportunities. In the Michigan Public Engagement Framework, we call these “domains.” Domains are often separated by different types of goals, stakeholders, experiences, or content knowledge. Many of them intersect, however, and a single project can span multiple domains. For example, faculty might create a community-engaged course (Community-Engaged Learning and/or Service) that involves their students working with elementary school youth in an afterschool program (Alternative, Informal, and Lifelong Learning) to create a public work of art (Performance, Exhibition, and Installation). Ultimately, these domains help us to conceptualize the range of opportunities available in the university public engagement landscape.

| Domain | Working Definition | Examples |

| Alternative, Informal, and Lifelong Learning | Connecting with learners of all ages in informal or nontraditional educational settings |

|

| Applied Practice and Consulting | Offering professional services, often on a pro-bono basis |

|

| Business and Entrepreneurship | Collaborating to create new products, services, or innovations |

|

| Capacity-Building Programs | Training and enabling stakeholders |

|

| Communications and/or Media | Sharing research-related information in various forms |

|

| Community-Engaged Learning and/or Service | Working directly with external stakeholders through academic courses, co-curricular programs, or volunteer projects to address community-identified needs |

|

| Community-Engaged Research | Working directly with external stakeholders on projects that address community-identified needs and drive research |

|

| Education and Educational Outreach for PreK-12 and Two-Year / Community College Students | Connecting with youth in formal school settings or educational programs |

|

| Holdings and Collections | Acquiring and negotiating physical assets held by the university |

|

| Performance, Exhibition, and Installation | Creating spaces or artistic works open to public consumption |

|

| Policy, Advocacy, and Government Relations | Engaging with all levels of government in order to inform policies and decisions |

|

| Residency Programs and Internships | Embedding individuals within an organization for exchange learning and work |

|

Additional details are found in the slide deck mentioned above. You can also view a recent #SciEngage webinar discussing this framework and the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s (AAAS) Typology for Public Engagement with Science, hosted by the National Academies of Sciences and AAAS.

How might we use the Michigan Public Engagement Framework?

We believe that the Michigan Public Engagement Framework allows us to accomplish a number of interrelated goals. First, it allows us to utilize a shared language and framework when discussing public engagement. This in turn helps to name and break down silos that might separate different types of public engagement activities.

Second, it points toward key practices in public engagement and enables stakeholders to identify and develop skills that are necessary for effective engagement, including effective communication and inclusive practices. It particularly helps people who are new to public engagement as they develop skills and consider the wide range of opportunities that are available to them.

Finally, the framework can inform assessments of public engagement activities by pointing to important relational variables and different areas of impact. Practitioners—including informal science educators, science communicators, and science policy professionals—have long grappled with ways to evaluate public engagement activities, and using a common language to assess these activities will help to recognize and reward the important work of engaging with different publics.

The content in this post was adapted from a series originally published in a blog by the University of Michigan Office of Academic Innovation. You can read more in-depth recaps of the meeting series that led to the development of the Michigan Public Engagement Framework in the series of posts below.

- Part One: What are the goals of the Conceptualizing Public Engagement series? (published 12/13/18)

- Part Two: How does our community define public engagement? (published 1/25/19)

- Part Three: What are critical issues that hinder effective public engagement within our community? (published 3/1/19)

- Part Four: The draft Michigan Public Engagement Framework (published 3/29/19)

- Part Five is coming soon and will outline next steps at the University of Michigan.

If you have further questions about this work, please feel free to contact me at eaurbach@umich.edu or on Twitter at @ElyseTheGeek.